THE “REEL” MCCOYExcerpts from "Herbert Solow:Discusses His Desilu & MGM Legacy"Interview by: Hadassah R. L. Broscova, Carpe Articulum Editor in Chief  Herb Solow (front row, 6th from left) outside of Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studios.

Herbert F. Solow. Nearly everyone in the industry claims to know him. He made many of them into stars–and put

the glimmer in the stardom of others. He was the heartbeat of Desilu and MGM Studios. Everyone knows him–or do

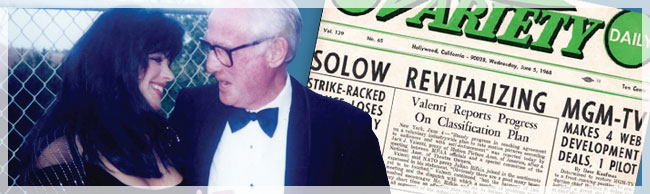

they? During this rare interview, this enigmatic man spoke candidly about his career, the people he worked with, and about his views on the film industry–from the inside looking out. Unlike so many people in the film world–both seasoned and neophyte–Herbert spoke with the authority of One Who Knows. And he does. The following interview was no mere Q & A. It was an interlude, and an education. He patiently walked me through the way things were, and the way things are now. He doesn't answer "personal" questions. But if you look closely, you will see that he doesn't have to. Herbert is a man of dignity. A man of his word. And if one pays attention, he or she will see the man emerge from between the lines of his answers like an elusive snow leopard from his den. One will see that for Herbert Solow, everything is personal. When he works, his whole heart is in it. When he is leading a film or television series to success, every fiber of his imagination and talent alights on the problem until it is solved. His whole life is Mission Impossible. Rarely has any man been surrounded by so much misinformation. What does he despise? Hypocrites. Charlatan journalism. Misquotes. People taking credit for other people's creative work. Uninformed people speaking about things they never witnessed and couldn't possibly know. And why shouldn't he? On more than one occasion, journalists have conducted interviews with people who were never there for the conversation quoted. How does Herbert know? Because only Herbert and two other men were present, and the other two are now dead! What does he love? His wife, Harrison, first and foremost. The creative process. Competence on the part of professionals. A great piece of film Fine Art. A very few close friends. In short, all the jewels he has accumulated over decades of hard work. All the beautiful things he has earned that would render any life enviable. Speaking of his wife Harrison, she is the most important contributor to his aforementioned happiness. The two are inseparable. Harrison is no trophy wife. She is a brilliant, accomplished writer, award-winning author, champion of the Arts, and oh, did we mention world-traveler, Welsh speaker and educator? See the article following this one to discover more about this face that could launch a thousand ships, but whose heart sets sail for one alone. The two of them together challenge traditional mathematics, for in this case, one plus one equals ten. The synergetic energy between them grows exponentially when they are near one another. They are life–long soul mates. Harrison is the only one Herb confides in. They are inspirational. Not the kind of inspirational that pulls at my rather infamous sardonic wit and cynicism. Rather, the kind of inspiration that imparts hope for the intelligent: that life–long love, while rare, is indeed documented among the more evolved of our species.  Harrison and Herb on the way to the Academy Awards. As for Herbert's larger-than-life career, let me detain you no longer. The man is responsible for the birth and early life of the most successful television series in history. And its birth will astonish you. Only Herbert's vision and talent could have turned a relatively unknown Gene Roddenberry and his crumpled page of manuscript into the tour de force we know today as Star Trek. Herbert Solow is truly that person who has gone before. Hadassah Broscova: You know we have to talk about Star Trek. I want to hear about the other things that were behind the scenes, however, instead of the normative star-perspective. Can we begin with the writing fiasco between Gene Roddenberry and Harlan Ellison? Herbert Solow: "We certainly can, Hadassah. But first two very short stories. Alexander "Sandy" Courage was a first–class film composer, arranger, orchestrator and conductor; Sandy worked with the very best of worldclass musical talent. However, the very mention of Sandy's name invites the comment, "Oh. He composed the Star Trek theme." Walter "Matt" Jefferies was a brilliant aviation artist, draftsman and motion picture set and prop designer; Matt worked on many important movies and television series, and his aviation paintings are highly prized by collectors. However, the very mention of Matt's name invites the comment, "Oh. He designed the Star Trek space cruiser, the USS Enterprise." So, please believe me, I'd be kind of curious if you had not begun our conversation with a question about Star Trek. It seems to override everything that Sandy did, Matt did and I did. “Harlan Ellison. Actually, any conversation about Star Trek and writing will always touch on Harlan Ellison, his [‘City on the] Edge of Forever’ and controversy...Harlan is a fine writer, an honorable writer and a close friend of mine. And of equal importance for validity sake, not only was I there at the time, but everyone on the original Star Trek series worked for me. That, I guess, makes me the authority. “Gene Roddenberry, on the other hand, who was not a good original script writer, turned out to be on the other side of honorable, and was only a close friend of mine when I was in a position at Desilu and MGM to hire him as a producer, or to adapt a book for the screen. “As we all know, Star Trek operated under a fairly strict television budget, in this case $195,000 [per episode]. Remember this was 1966. Harlan's first draft script budgeted out in the area of $235-240,000. Since television budgets contained very little soft money, a simple polish was not in the cards, and Harlan, a highly experienced screenwriter, was personally prepared to do what had to be done to alleviate the budget problem. So Gene telling Harlan he was personally ‘fixing’ Harlan's script was the opening skirmish of the ‘City on the Edge of Forever’ war, so to speak. There have been–are–many ‘experts’ who have theories about the war... I'd take a lot of them with a small grain of [salt]. If you have to root for one side to win this war, I'd go with Harlan. “Important to any discussion of the two men, Harlan disliked Roddenberry enormously. They differed on business ethics, morals, values and, of course, talent. One was on the side of right; one wasn't. It isn't hard to guess who was who. “At the Writer's Guild Award Dinner that year, Harlan was at a table with his writer friends rather than at my table along with the series' producers. When ‘City on the Edge of Forever’ was announced as winning the best television script award (the award, by the way, is based on the writer's original draft, not the script as revised by others and filmed), Harlan stood up and proclaimed, ‘Don't let THEM rewrite you,’ much to the applause of all the writers at the dinner. I must admit that I joined in with the applause.”

SCREENWRITING CONTROVERSY RODDENBERRY/ELLISONAcknowledged as the best single episode of Star Trek, “The City on the Edge of Forever” also was the show's most divisive. Written by the ferociously talented, mercurial Harlan Ellison, the original script follows a corrupt officer on the Enterprise named Beckwith who deals in drugs—literally, narcotics of sound. In trying to elude capture, Beckwith transports back to old Earth through a “time vortex” on an alien world and changes history. With the future altered—the Enterprise is now a predatory battleship called the Condor—Kirk and Spock, with the help of the ancient, monolithic Guardians of Forever, go back through time to stop Beckwith. On Earth circa 1930, they meet a WWI veteran named Trooper and a social visionary named Sister Edith Keeler. Keeler is the focal point in time. Intended to die, she will be saved from a fatal tra!c accident by none other than Beckwith, changing history...unless Kirk and Spock can stop him. But Kirk has fallen in love with Keeler. At the pivotal moment, Kirk freezes and it is Spock who intercepts Beckwith as Keeler is killed, hereby correcting the course of time. Robert Justman, co-producer of Star Trek, loved the episode—but agreed with Roddenberry that it was too expensive to be filmed. Now starts the controversy. The amount of the potential cost overrun is disputed by Ellison. Roddenberry sends the script through several rewrites from several rewriters. Ellison is livid. (He shares his side of the story in his incendiary The City on the Edge of Forever: The Original Teleplay That Became a Classic Star Trek Episode.) A vastly revised script, directed by Joseph Pevney, is filmed at last with Joan Collins as Keeler. Beckwith is gone; in his place, Dr. McCoy accidentally injects himself with a powerful stimulant that causes intense paranoia. It is he who escapes into Earth's past and changes history. The Condor subplot is erased, as is Trooper. Still, the episode gets raves and ultimately wins a Hugo Award. Ellison, however, wins the Writer's Guild top screenplay award—for his original script. In the years and decades that follow, Roddenberry publicly states, numerous times, that the revisions had to be made because Ellison “had Scotty dealing drugs” and because the original script's budget was, he says, tens of thousands of dollars too high. Among the people who dispute Roddenberry's version: Herb Solow, the Desilu executive in charge of Star Trek's production. In his book with Justman, Inside Star Trek, Solow details the trek of “City” from inception to filming to aftermath.

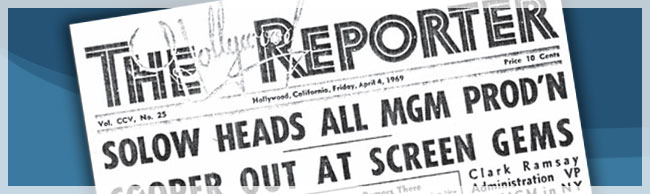

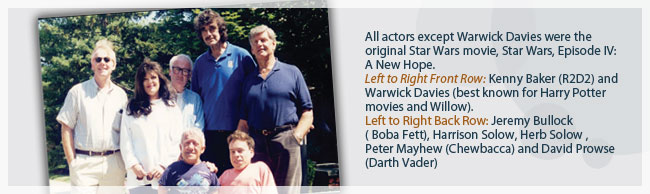

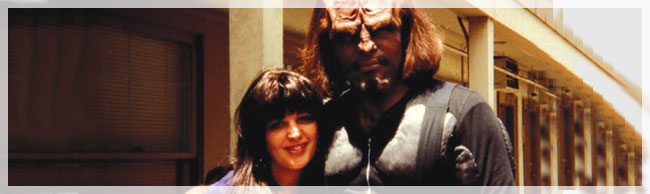

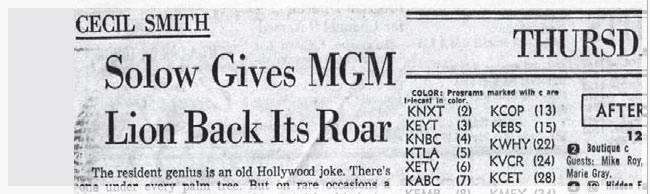

Hadassah Broscova: Tell me about the creative process while developing Star Trek with Gene Roddenberry. It must have been a pivotal time, deciding how to go about all of this. Can you tell me about the early development? Herbert Solow: “[Roddenberry] had this idea for a show. It was only an idea, a little Buck Rogers, a taste of Flash Gordon, a bit of Isaac Azimov, etc. I liked it even if several of his characters were badly drawn. The Mr. Spock character, for example, had not only pointed ears, but a long tail and was red! He was the devil! A lot of Gene's thinking was very obvious. And much of it were ideas “borrowed” from less obvious sources ie. Twilight Zone, several 1950 MGM movies like Forbidden Planet and even from a 1939 cartoon.  Harrison with Nichelle Nichols, who played Nyota Uhura, Lieutenant,

“What I liked about it was everything, characters, ranks, procedures, the ship, etc. was based on the United States Navy, which I thought made it so much easier for audiences to grasp and understand. Bear in mind that if you're watching a new television series that's about a rancher, for example, you're not quite sure what a rancher does all day every day. But if you're watching a show about a police officer, you know exactly what he or she does. The audience can relate better and better enjoy. So I thought that by defining the people aboard this space vehicle as members of the Navy—we had captains, we had admirals, we had yeomen, we had ensigns, could only be a plus. I also felt we could also use this approach to tell more human stories, as opposed to merely telling 1950s, 1960s science fiction stories about alien monsters and creatures and such. “I made a key change whereby we treated every episode, the whole series, as a flashback and invented Star Date. This became very important to the understanding of our stories and, I strongly believe, eventual success of all the television series and movies. A flashback is very interesting. People become kind of relaxed with the characters and the story knowing what they were watching had already happened. We're not dealing with the future, absolutely not, we're dealing with telling a story from the past. The Captain's Log setup each show. Bottom-line, telling the story from the past was a huge plus. “Gene and I actually made a lot of changes; we made some very weird changes and then came top our senses and changed back again and then made more changes. And finally we were ready to take it into the marketplace. Oddly, CBS turned down Star Trek, which many of people don't realize. Without telling me, and without knowing the changes I had made, a Desilu executive along with Roddenberry's agent went ahead and approached CBS on the idea. They turned it down because they had a series called Lost in Space. Actually, not knowing our changes, I don't think they really understood the revised concept of the series. It was actually a happy day for me as I was able to offer it and sell it to Grant Tinker and my other friends and former associates at NBC. “Though Gene was very nervous at the outset and during our development process, his one piece of wrinkled paper became many pieces of neat bound paper. It wasn't until after we made the second pilot, when I sold it to NBC as a going series, that Roddenberry made what's called 'the series' bible”: information on all the characters, how they relate to one another, an indication of sample stories, the goal of the series, et cetera. But at the beginning, it was just a plain wrinkled piece of paper!” Hadassah Broscova: What about Gene Roddenberry personally? What were your impressions of him? Herbert Solow: “As I mentioned, Gene came in very nervous, obviously he had little experience pitching ideas to potential buyers. He also had little experience working in the television industry; he had created a short—lived television series at MGM called The Lieutenant, starring Gary Lockwood, as a Marine Corps officer. Other than that, he was a kind of mediocre freelance writer for several westerns and police series. His real prior experience? He was a police officer for the L.A.P.D., before that, he was an airline pilot for PanAm. Hadassah Broscova: Howard Hughes owned PanAm at that time, I believe. Herbert Solow: “Actually, Mr. Hughes also owned the studio when it was RKO, before it became De, before getting in the cockpit of a PanAm aircraft on a night flight from New York to London, that he fell asleep at the controls! “As I've said, Gene was very nervous and soft—spoken when we first met, and, I quickly gathered, not that experienced as a producer and not that responsible as an individual!” Hadassah Broscova: Moving over to your days at MGM as Head of the Studio and being in charge of Worldwide Motion Picture and Television Production, was television still considered an unwelcomed intrusion into the movie business, particularly causing an erosion of box office receipts? Herbert Solow: “Though producer, Darryl Zanuck had said years earlier, that people would tire of sitting at home and watching movies playing in a plywood box—the exact opposite happened. People by the millions stayed home and watched movies in a little better than a plywood box. But they stayed home. I recall the first time we made a two—part episode on Mission:Impossible, without telling the viewers that they would have to return the following Saturday night to see the conclusion of the exciting story. The following Saturday night was not only a huge rating night for Mission, it was also a very disapppointing box office night for the movie business throughout the country.  The Hollywood Reporter—April 1969. “But it was also the beginning of television payback time. And it came in the form of studio space and keeping the highly experienced and professional Hollywood production people working. And it came at a time when a lot of movie production traveled to distant locations and used foreign crews, leaving behind empty sound stages and idle crews, “At Desilu, for instance, we had no budget to travel the world making the afore mentioned Mission:Impossible series, a series that depended on foreign backgrounds. Star Trek also depended on foreign locations, so to speak, and we certainly weren't going to Talus IV to film an episode. Actually, some people I spoke with thought we had filmed the second pilot “on location.” I didn't have the heart to tell them we had filmed it at the Desilu Studio in Culver City, California. Mannix was an American detective series and filmed locally. At MGM, we made Medical Center and the Courtship of Eddie's Father, both needing local sound stages, crews and other production facilities. I also think television forced the movie business to move in different directions so far as types of films produced, audience demographics and budgets. Today, television is a welcome and necessary partner in the Hollywood production business. Who knows, someday an episode of Star Trek or a Star Trek movie may actually be filmed on Talos IV. Hadassah Broscova: ...And the next question is with regard to literacy in the United States, I'm kidding, of course, (laughing) Heaven and Earth! You are a much kinder person than I am, I'm afraid! Herbert Solow: “Listen, Hadassah—there's enough trouble in the world. I don't need that. I'll go along with them. Hadassah Broscova: What was your experience working with Lucille Ball? Herbert Solow: “I was head of Daytime Programs on the West Coast for NBC when [Desilu] called and they asked me to come over, to oversee the development of new television series. The studio had kind of run into hard times, and all they had was Lucy's own show. So I said yes, left NBC, went over to Desilu and found they had no idea what they were doing. “Lucy and Desi had divorced a few years earlier. Desi was a very talented guy. All the creative people on the lot, from directors, writers, wardrobe people, makeup, the film editors, loved working with Desi. He was creative, and he was very exciting. But when he left the studio after the divorce, there was a very big gap to fill, and the studio had really fallen on hard times. And Lucy wanted to get back in the television series business. “I reported to the studio, went to Stage 12, which is where Lucy did her show, and found Lucy rehearsing the latest episode. And Lucy was...kind of a cold, business—like person when it came to anything happening on her stage...she ran the place! There was a director, and there was a producer and everyone else, but Lucy was in charge. Without a doubt everyone's very clear understanding was Lucy is the boss of Stage 12...And all she said to me was, ‘Get me some shows!’ All I said to her was, ‘Thank you, I will, goodbye!’ “And I went to work and was very fortunate, because within a year I had three one—hour shows on the air: Star Trek, Mission:Impossible and Mannix. Happily, Lucy never involved herself in any of the shows. I sent her the three pilot scripts before we shot the pilots. She did not read Star Trek, because she said she ‘did not understand that stuff.’ She read Mission: Impossible and thought the script was nice; and she read the Mannix script and had no comment. She did not pester me with any casting ideas, with any director ideas, with any crew ideas. She took care of her show. Lucy very much cared about her studio but left me alone. She went to work on her stage, Stage 12; I went to work in my office on the second floor of the Administration Building..  Variety—July 1996. “Once in a while she would come up to the office, and my secretary, Lydia, would announce, ‘Miss Ball is here.’ And I'd say, ‘Well, send her in.’ Lucy would then walk into the office and say, ‘Remember me? I'm the girl from Stage 12!’ I'd say, ‘Well, hi there, how are you!’ She'd ask, ‘Everything all right?’ I'd say, ‘Lucy, everything is fine, goodbye!’ And Lucy would turn around and leave. It was a great working, or non—working, relationship. Occasionally I would drop into Stage 12 on Thursday nights and watch Lucy film the following week's episode before a live audience. “Lucy was a taskmaster, tough on her own show. She was a very talented woman who knew what she liked, knew what she wanted, and was going to get the best from the people around her. But when it came to the rest of the studio, she had nothing to do with development, sales or production.” Hadassah Broscova: It is amazing that you two worked in such relative close proximity and yet so autonomously. She does sounds as though she was a hard business woman. Quite different from the quirky, happy—go—luck character she portrayed on television. Are there any other specific memories about her that stand out in your mind? Herbert Solow: “Here's an interesting story about Lucy. As I said, she was not involved in anything I was doing. I sent her a couple of notes saying, this is where we are on development, this is what we are doing, . I rarely heard from her about anything. She sent me one note in four years, saying, ‘Thank you for sending me the report to me.’ That was it! “However, she had heard, when I was casting the Mission: Impossible pilot that there were five main parts to fill, and one was for a woman named Cinnamon Carter...that we had hired Barbara Bain—or we were about to hire Barbara Bain—while another part was a character named Rollin Hand, who was to be played by Martin Landau. Now, Lucy heard that Martin Landau and Barbara Bain lived together (the fact is they were married.) And right away, Lucy got nervous. She didn't call me. She called my casting director and said, ‘Could you please ask Miss Bain if she would come to see me.’ So the next time Barbara was on the lot—remember, she still hadn't been formally cast—she went down to see Lucy and Lucy spoke to her, and I heard back through the casting guy that Lucy was very happy with Barbara. Now the reason for speaking with Barbara was that Lucy had had problems with Desi when it came to carousing. And Lucy wanted to make sure it wasn't the same thing going on between Marty and Barbara. That was her only concern. As Lucy later told me, she'd had enough of that carrying—on years earlier when Desi was at the studio. She didn't want any of that going on in her studio! Lucy was very definitely concerned with the Desilu image. “We did have a problem with Desilu image and Gene Roddenberry. Lucy heard there were some afternoon and late night goings—on in Gene's office. Which, in fact, there were. It was sort of common knowledge within the Star Trek production unit. And Lucy wanted him thrown off the lot!  Some cast members from Star Wars, Episode IV, The New Hope. “I said, ‘Lucy, we're not going to do that. NBC wouldn't mind, but the fans would be up—in— arms after Gene told them how Desilu was preventing him from producing his intelligent series. (the usual Roddenberry self—promotion technique of blaming any personal short—comings on NBC or the studio.) I'll speak to him and make sure that doesn't happen again.’ And as Lucy agreed, she strongly repeated, ‘Not in my studio!’ You have to admire her for very firm and moral stand . It was her name on the studio sign. When you think of Desilu, you only think of Lucy, and she just didn't want any carryings on in her studio. She was certainly entitled. And so I spoke to Gene and put a stop to it—I think! I'm not sure! Probably not.” The conversation turned to ethics and guidelines instituted by the Motion Picture Business and how they have changed over time. It also turned to Bollywood and I mentioned that two of my favourite movies of all time came from that particular genre, primarily the film Kabhi Kushi Kabhi Gam. I liked this one because it enters into the world of verbal/ non—verbal love between a father and a son—a subject rarely excavated in Western Literature or film. I mentioned that it was lovely to see such wildly successful films that weren't based on sex and violence. He mentioned that the reasons for this were two—fold. One, that the Indian and Indian—American public strongly support the films as they come out, as opposed to the American market which is fiercely competitive (citing television specifically due to the fight for ratings). Secondly, that they are more peaceful people in general and have reflective laws prohibiting sex and too much violence. Hadassah Broscova: My brother and I—he is a very wise person—had a conversation about American culture and film and he said ‘America is one of the most violent and blood—thirsty cultures ever. ’I had to think about that, but after he pointed out what sells at theatre, America's lust for violent sports, etc., I was forced to agree. What are your thoughts on this, and the way the things have changed in film over the years? Herbert Solow: “He's right! Absolutely he's right. I've worked in Italy. I've worked in France, Yugoslavia, England of course, Ireland, have lived in Wales, and am associated with all of these cultures, and they are, for the most part, pleasant, peaceful loving people—not all of course—but here? Unfortunately, we think violence. If you are moving into a new neighborhood the first thing you do is check local crime reports, in hopes that is not too violent in an area. We have millions of guns out there. And audiences like their entertainment in the same pattern...audiences, in fact, demand it. But I have to tell you, if you look at some of these film ratings and check out box—office grosses from overseas, you say, ‘you know, they kind of like those kind of films, also.’” Hadassah Broscova: Rarely is a film as good as the book. Frankly, I can think of only two book—to 'film endeavors which were true to the writing. One was Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove (made into a mini' series) starring Tommy Lee Jones, Robert Duvall and Angelica Huston etc., and the other was Age of Innocence with Michelle Pfeiffer, Winona Ryder and Daniel Day Lewis etc. Honestly, I think it was because the filmmakers actually read the book! There are a great deal of Screenwriters and Novelists in our readership. Can you shed some light on what they can expect control—wise, if they sell their book to be made into film? Is there a waymto negotiate the control needed to maintain the integrity of a story? So that the visual story of a book is in fact reflective of what the original vision was?  His wife, Harrison Solow with actor Michael Dorn “WORF” of Star Trek:The Next Generation Herbert Solow: “The bottom line is this: It's who has the power and who has the control, and 95 percent of the time it is not the author of a book. When you hire a director, a quality director, it will always become the director's vision of the book. The author may talk to the director, and the director will understand the book, but he or she knows what they see in the book, and that's the film the director will make. “There are reasons for certain people in the cast. One is the box office, the main reason, of course. In many instances, someone will be cast in a role for almost unexplainable reasons, not necessarily because that person is exactly right for the part. We've seen that happen in both films and television series. We've seen studios buy the movie rights to a book, toss out the contents and only use the title. “The only time that an author of a book has control is when that person, that author, pursues a deal with the studio and says, ‘I want control!’ and the studio agrees. Most times, however, that's not going to happen; the author will be turned down. And it finally gets to the point of, ‘Okay, I want the deal...it's more important to me than control. Here's my book. Don't harm it too much!’” “I must also point out that many authors don't understand the intricacies of the movie business, what is needed and, more importantly, what isn't needed. When you think about various situations where even experienced screenwriters many times see their work severely changed, you know that most book authors don't have a chance. Very few directors, very few, will listen to an author's plea, ‘I think you're doing this wrong, or I think the casting should be such and such.’ Or that a subplot, or minor character is highly important to the story and must be retained.’ As they say, ‘It aint't gonna happen’. “Story: I worked with a brilliant book and short story writer named Theodore Sturgeon. Teddy had screenwriting experience contributing to various television series as well as several episodes of the original Star Trek. Teddy and I were adapting one of his novellas. Killdozer, for a major two hour television movie that I was also producing. Two of the “rules of the road” I had laid out to Teddy were, one: don't spend a lot of screen time on characters who are only incidental to the plot. Television is a personal medium so stay with the important characters and the main plot. And, two: there are no open-ended budgets in television so we must spend the money wisely. Especially with a project like Killdozer as the special effects and optical effects (before CGI) were very important to the plot. And, unfortunately, they were very expensive. Several weeks later and Teddy came in with several pages including the opening to the movie. It went along the lines of: FADE IN. A flight of pterydactyls soars over this small Pacific atoll and swoops to a landing among other pre-historic creatures. I looked closely at Teddy and pointed out that, with that one optical effect, we just spent our entire optical effects budget. “Remember my rules for the road, Teddy?” To which Teddy replied, “But, Herb, you said to concentrate on the important characters.” “That I did, Teddy, but pterydactyls have nothing to do with the basic plot.” “I understand that, Herb, but I think the pterydactyls are important characters.” I ended up adapting the novella; the movie has become sort of a cult classic.  Screen credit from the original Star Trek television series. Hadassah Broscova: That's very enlightening, and pretty sad, frankly. But that is the price of fame, I suppose. Mr. Solow—please tell the screen—writers what the truth is about the industry today. Screenwriters want to know what the reality is for prospective work. Herbert Solow: “I don't think I can honestly define the truth in today's film industry as I'm not involved in it on a daily basis, spending most of my time writing a new book and critiquing other's screenplays. But I can make a comment about the many people who write screenplays, especially the neophyte screenwriter. “Years ago everyone who writes looked to write the great novel. Today, it seems everyone who writes looks to write the great screenplay. So, tell me. What does the industry do with all those great screenplays? There are a limited number of studios these days making a limited number of films hoping to release them via a limited amount of television broadcast time and, more importantly, a limited number of movie theatres. “What happens? A great many people, the earnest writers who honestly feel they have talent and ability want some guidelines, some help, some criticism and end“up going to a college or a writing school. And what has happened over the years is that the colleges and universities suffering through periods of low enrollment or recession and needing more money, will say, ‘Ah, we know how to get more money. We'll have a creative writing department and teach screenplay writing or add screenplay writing to our already existing creative writing department!’ “If that's your route, please remember that there are (real) Writing Schools where true professionals offer their talents and guidance. And then there are writing schools where non-professionals read a couple of books on ‘ How to Write Screenplays’ and are overnight experts having never stepped on a sound stage, written a screenplay, made a movie, etc. and they're going to show you how to write screenplays. Right! “Unfortunately, even after completing a screenwriting course at a quality institution, that's when its realized that there are very few jobs out there, especially when considering the thousands of hopeful writers with one or more screenplays clutched in their hands, the difficulty in getting an agent to represent you and your screenplays, the reluctance of studios to read literally tons of screenplays, etc. Am I painting a bleak picture? Absolutely. But for reason. Those young screenwriters who have true talent, who have confidence in that talent and have the character and drive to push the career, they have a shot at breaking through the seemingly negative barrier. And, believe me, it's worth it. However, for all the rest, after you graduate from your writing course and announce to the world that you're available, please don't be surprised if the phone doesn't ring.  An article by Cecil Smith in the Los Angeles Times. Hadassah Broscova: You have personally read hundreds of scripts and have written some yourself, have you not? You are a renaissance man in this way. Herbert Solow: “Well, not really. I'm more the guy who knows that if I'm to sit with quality screenwriters such as Howard Rodman, Dennis Potter, Robert Bolt or our good friend Harlan Ellison and discuss their first drafts or sit with quality directors such as David Lean, Bobby Altman, Herb Ross or Blake Edwards and discuss their first cuts, I sure had better know what I'm talking about. So, I've written scripts, and I've edited hundreds [of scripts] as a member of the Writer's Guild of America. I've also directed and am a member of the Director's Guild of America. “I think there is an inherent problem in the producing process of both television films and movies whereby many studio and network executives do not know how creative people think and what creative people do or are supposed to do or aren't supposed to do. It's easy to understand why they should not expect a degree of respect. I think most executives should have experience in the various creative fields, so that when they deal with creative people, they can be on the same page and can relate to one another as professionals. I know from years of experience, that approach avoids an awful lot of problems. “I was fortunate in going from college to working in a talent agency mailroom, the William Morris Agency in New York, and learning that world, and then going into syndicated television programs at NBC and then into daytime programs at NBC and CBS, and on to the studios—Desilu, Paramount Television and then MGM. If you're alert, you can't help but realize what's around you and pick up as much as you can from dealing with everyone. That's everyone. From the guy who makes the coffee on the set to the guy who owns the studio and writes your checks. They all count.  Herb and Leonard Nimoy at a speaking engagement. Mr. Solow, this has been a profoundly illuminating interview, on all accounts. I have to admit that I am rethinking some of my former ideas on my own field, after hearing some of your answers. Some of them thought-provoking and inspiring, others engaging and informative, and some of them sobering. We at Carpe Articulum—all of us—thank you for your precious time and attention. The insights were invaluable and there is something here for everyone to Lucy fans to Trekkies to die—hard serious writers. This is a rather enchanting insider's view of the industry. It is our pleasure to have met you and your amazing wife, Harrison. So much career and life momentum leaves one breathless, wondering “gracious, what's next?” Herbert Solow: “Actually, Hadassah, next is finishing the book I mentioned. It's called Going Solow, and, as a professional memoire, covers my many years in the television and motion picture business basically through stories and anecdotes about the many famous people I've met along the way. I'm actually surprising myself to find it's so interesting and entertaining. If I wasn't writing it, I'd buy it when it comes out. Mr. Solow, thank you so much for your time and dedication to this interview. You are a true legend in your own time. Frankly, your work ethic, determination, dedication to Art and its perfection, and stalwart honesty are all the hallmarks of an endangered species that single—handedly made this country great. I am deeply disturbed and even on occasion disgusted with this replacement generation (obvious exceptions exist) clogging around in their predecessors ' shoes, five sizes too big, like children playing dress up. If only—if only—your generation was the starting point for this country, rather than its high water mark! Imagine what might have been accomplished, standing on the shoulders of giants. He and his wife, author Harrison Solow, live and work in California and Wales (UK).  Herb and Harrison confide intimately in Herbert's amazing orchid garden solarium. Page updated on August 30, 2012

|